Decompiling the New C# 14 field Keyword

Properties in C# are a powerful tool for encapsulating data inside a class. They let you specify getter and setter logic that’s automatically applied when reading from or writing to the property. They’ve been supported since C# 1.0, which required manual backing fields for storage. C# 3.0 then introduced auto-implemented properties to remove these boilerplate backing fields. However, it came with a trade-off: if you needed custom logic in your get or set method, you still had to use a manual backing field.

C# 14 introduces the new field keyword, which combines the flexibility of a manual backing field with the simplicity of an auto-implemented property. In the sections that follow, you'll see how the compiler handles this new keyword in practice. We'll also cover some important caveats to keep in mind as you start using it.

A Brief Overview of the field Keyword

Before C# 14, backing fields were necessary whenever a property needed logic beyond just retrieving and setting a field value. The snippet below demonstrates how a manual backing field is required for the Email property, since it cleans up the incoming value before storing it:

public class User

{

// Auto-property: simple getter and setter

public string Name { get; set; }

// Field-backed property: more complex getter and setter

private string _email;

public string Email

{

get => _email;

set => _email = value.Trim().ToLower();

}

public User(string name, string email)

{

Name = name;

Email = email;

}

}Auto-implemented properties are convenient for simple scenarios, but as shown above, they fall short when you attempt to add custom logic. The new field keyword in C# 14 fills this gap. It lets you keep your code concise, while still allowing for custom logic in your property accessors.

The above snippet can be simplified in C# 14 as follows:

public class User

{

public string Name { get; set; }

- private string _email;

public string Email

{

- get => _email;

+ get;

- set => _email = value.Trim().ToLower();

+ set => field = value.Trim().ToLower();

}

public User(string name, string email)

{

Name = name;

Email = email;

}

}Notice how the manual backing field is no longer needed. But what actually happens behind the scenes? In the next section, we'll look at the disassembled Intermediate Language (IL) code to see exactly how the compiler handles the field keyword.

Inspecting the IL Code

To demonstrate how the compiler handles different implementations of properties, we’ll use SharpLab to examine the following code snippet, which contains a standard auto-implemented property (Name), a manual backing field (Email), and the new C# 14 property implementation (Username):

public class User

{

// Auto-property: simple getter and setter

public string Name { get; set; }

// Field-backed property: more complex getter and setter

private string _email;

public string Email

{

get => _email;

set => _email = value.Trim().ToLower();

}

// New C# 14 'field' property

public string Username

{

get => field;

set => field = value.Trim().ToLower();

}

}You can view the compiler-generated code for this example on SharpLab. When you examine the IL code, you'll see how a property using the field keyword is very similar to an auto-implemented property behind the scenes.

Identical Backing Fields

When you use the field keyword, the compiler automatically creates a private backing field. This generated field is identical to what you'd get with a standard auto-implemented property.

Here is the IL code for the standard auto-implemented property, Name:

.field private string '<Name>k__BackingField'

.custom instance void [System.Runtime]System.Runtime.CompilerServices.CompilerGeneratedAttribute...

.custom instance void [System.Runtime]System.Diagnostics.DebuggerBrowsableAttribute...And here’s the IL code for the C# 14 field property, Username:

.field private string '<Username>k__BackingField'

.custom instance void [System.Runtime]System.Runtime.CompilerServices.CompilerGeneratedAttribute...

.custom instance void [System.Runtime]System.Diagnostics.DebuggerBrowsableAttribute...In both cases, the compiler takes the same approach:

- It uses the same

<Property>k__BackingFieldnaming format for the underlying field name. The angle brackets make the name illegal in C# source code, preventing naming conflicts between user code and compiler-generated code. - It adds the

CompilerGeneratedattribute to mark the field as an artifact of the build process. - It adds the

DebuggerHiddenattribute to hide the field in the debug window.

The Getter Implementation

All three properties have simple get implementations that return the underlying field value. If you look at the IL code for each, you'll see they're essentially the same, except that the Email property uses the manual _email field, while the others use a compiler-generated field.

Here’s the get method for the Email property, which uses a manual backing field:

.method public hidebysig specialname instance string get_Email () cil managed

{

// ...

IL_0000: ldarg.0

IL_0001: ldfld string User::_email

IL_0006: ret

}And here’s the get method for the Username property, which uses the field keyword:

.method public hidebysig specialname instance string get_Username () cil managed

{

// ...

IL_0000: ldarg.0

IL_0001: ldfld string User::'<Username>k__BackingField'

IL_0006: ret

}Both sets of instructions do the same thing: they load the value from the backing field and return it. The only difference is which field is used to store the value.

The Setter Implementation

How about the set method implementation? Both the Username and Email properties perform processing on the incoming value before storing it.

Here’s the IL code for setting the Email property, which uses a backing field:

.method public hidebysig specialname instance void set_Email (string 'value') cil managed

{

// ...

IL_0000: ldarg.0

IL_0001: ldarg.1

IL_0002: callvirt instance string [System.Runtime]System.String::Trim()

IL_0007: callvirt instance string [System.Runtime]System.String::ToLower()

IL_000c: stfld string User::_email

IL_0011: ret

}Then, here’s the set method for the Username property:

.method public hidebysig specialname instance void set_Username (string 'value') cil managed

{

// ...

IL_0000: ldarg.0

IL_0001: ldarg.1

IL_0002: callvirt instance string [System.Runtime]System.String::Trim()

IL_0007: callvirt instance string [System.Runtime]System.String::ToLower()

IL_000c: stfld string User::'<Username>k__BackingField'

IL_0011: ret

}In both code snippets:

- The method loads the current class instance onto the stack

- It then loads the incoming

valueparameter on the stack - It performs the processing on the

valueparameter, in this case, trimming the string and converting it to lowercase - It updates the underlying field with the processed value.

This shows that the field keyword is purely syntactic sugar. When you compile your code, it produces the same underlying IL code as manual and auto-implemented properties.

Potential Pitfalls to Consider When Refactoring to the field Keyword

Before you start refactoring your codebase to use the new keyword, there are a few important caveats to keep in mind. While the underlying IL code is essentially the same, how your code accesses the backing field can affect your application in subtle ways.

Magic Strings and Reflection Will Break

If you use reflection to access private members, removing manual backing fields in favour of compiler-generated fields will break reflection. This is because the underlying field name changes. As shown above, the compiler uses a mangled naming convention, such as <Property>k__BackingField, for compiler-generated fields. If your code, or libraries you use, rely on finding a specific private field by name via reflection, it will crash at runtime when you refactor your code.

The sections below highlight two common scenarios where reflection might cause issues: Entity Framework Core and AutoMapper.

Entity Framework Core

EF Core supports writing to private fields in a class using reflection so that you can bypass logic in your property’s set method when hydrating the entity.

For example, say you refactor your EF Core model class by utilizing the field keyword:

public class OrderLineItem

{

- private int _quantity;

// …

public int Quantity

{

- get => _quantity;

+ get;

set

{

ArgumentOutOfRangeException.ThrowIfNegativeOrZero(value);

- _quantity = value;

+ field = value;

}

}

}If your EF Core configuration class references the field by name, it will fail since the field doesn’t exist anymore with that name:

public class OrderLineItemConfiguration : IEntityTypeConfiguration<OrderLineItem>

{

public void Configure(EntityTypeBuilder<OrderLineItem> builder)

{

// …

builder.Property(p => p.Quantity)

.HasColumnName("quantity")

.HasField("_quantity");

// ...

}

}Here’s an example of the exception you can expect to see in this scenario, which reports that EF Core cannot find the underlying field for the property.

System.InvalidOperationException: The specified field '_quantity' could not be found for property 'OrderLineItem.Quantity'.

at Microsoft.EntityFrameworkCore.Metadata.Internal.PropertyBase.GetFieldInfo(String fieldName, TypeBase type, String propertyName, Boolean shouldThrow)

at Microsoft.EntityFrameworkCore.Metadata.Internal.InternalPropertyBaseBuilder`2.CanSetField(String fieldName, Nullable`1 configurationSource)

at Microsoft.EntityFrameworkCore.Metadata.Internal.InternalPropertyBaseBuilder`2.HasField(String fieldName, ConfigurationSource configurationSource)

at Microsoft.EntityFrameworkCore.Metadata.Internal.InternalPropertyBuilder.HasField(String fieldName, ConfigurationSource configurationSource)

at Microsoft.EntityFrameworkCore.Metadata.Builders.PropertyBuilder.HasField(String fieldName)

at Microsoft.EntityFrameworkCore.Metadata.Builders.PropertyBuilder`1.HasField(String fieldName)

at EfCoreFields.OrderLineItemConfiguration.Configure(EntityTypeBuilder`1 builder) in C:\Code\EfCoreFields\EfCoreFields\OrderLineItemConfiguration.cs:line 16

at Microsoft.EntityFrameworkCore.ModelBuilder.ApplyConfiguration[TEntity](IEntityTypeConfiguration`1 configuration)

at InvokeStub_ModelBuilder.ApplyConfiguration(Object, Span`1)

at System.Reflection.MethodBaseInvoker.InvokeWithOneArg(Object obj, BindingFlags invokeAttr, Binder binder, Object[] parameters, CultureInfo culture)This error only appears at runtime and not build time, so you’ll have to carefully update your EF Core entity configuration files as you refactor your model classes.

Fortunately, fixing your EF Core configuration classes is straightforward. Instead of looking for the backing field by name, you instruct it always to access the property using its underlying backing field with the UsePropertyAccessMode method:

public class OrderLineItemConfiguration : IEntityTypeConfiguration<OrderLineItem>

{

public void Configure(EntityTypeBuilder<OrderLineItem> builder)

{

// …

builder.Property(p => p.Quantity)

.HasColumnName("quantity")

- .HasField("_quantity");

+ .UsePropertyAccessMode(PropertyAccessMode.Field);

// ...

}

}This approach avoids hardcoding a field name. By removing HasField, EF Core reverts to its default conventions, which are capable of locating the compiler-generated backing field. The UsePropertyAccessMode method then ensures EF Core uses the located field rather than the property.

AutoMapper

A similar issue exists when using object mappers that rely on reflection, such as AutoMapper. For example, consider the following class, which has been refactored to use the field keyword:

public class Product : AuditableEntity

{

- private decimal _price;

public int Id { get; set; }

public string Name { get; set; }

public decimal Price

{

- get => _price;

+ get;

set

{

AuditPropertyChanged("Price", field, value);

- _price = value;

+ field = value;

}

}

}It’s possible that your AutoMapper Profile class still refers to the old field by name, which will cause issues:

public class ProductProfile : Profile

{

public ProductProfile()

{

ShouldMapField = fi => !fi.IsDefined(typeof(System.Runtime.CompilerServices.CompilerGeneratedAttribute));

CreateMap<CreateProductDto, Product>()

// Hard-coded field name in the string below

.ForMember("_price", opt => opt.MapFrom(src => src.Price))

.ForMember(dest => dest.Name, opt => opt.MapFrom(src => src.Name));

}

}Whenever you try to map objects or validate your configuration, you’ll run into an exception similar to this:

System.ArgumentOutOfRangeException: Cannot find member _price of type AutoMapperFields.Product. (Parameter 'name')

at AutoMapper.Internal.TypeExtensions.GetFieldOrProperty(Type type, String name)

at AutoMapper.Configuration.MappingExpression`2.ForMember(String name, Action`1 memberOptions)

at AutoMapperFields.ProductProfile..ctor() in C:\Code\AutoMapperFields\ProductProfile.cs:line 12

at System.RuntimeType.CreateInstanceDefaultCtor(Boolean publicOnly, Boolean wrapExceptions)The best solution I’ve found for finding reflection-based mapping issues is to assert your mappings at application startup. That way, you can find invalid mapping configurations as soon as your application starts, rather than when the actual mapping occurs.

var app = builder.Build();

// …

app.Services.GetRequiredService<IMapper>().ConfigurationProvider.AssertConfigurationIsValid();

// …

await app.RunAsync();If you want to avoid this issue altogether, consider using a source generator library like Mapster. That way, mapping issues can be caught at build time rather than at runtime.

Be cautious when using magic strings and reflection. These patterns can make your codebase fragile and more likely to break during refactoring, such as switching to using the field keyword.

The field Keyword Is Restricted to the Property

When you declare a private backing field, that variable is available throughout the class. The field keyword, on the other hand, is only available inside the property's accessor methods.

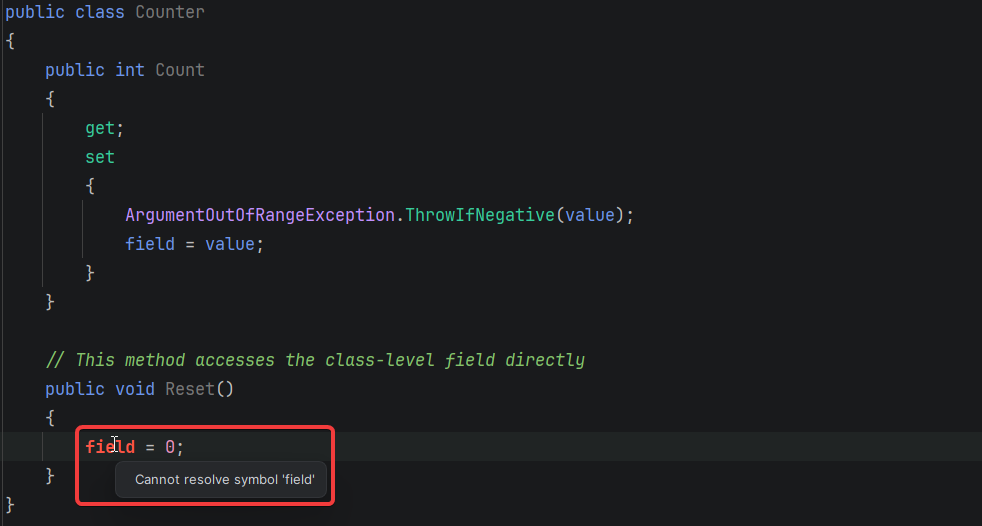

This can cause issues if you have methods that need to directly manipulate the underlying field value. For example, take a look at the Reset method in the class below:

public class Counter

{

private int _count;

public int Count

{

get => _count;

set

{

ArgumentOutOfRangeException.ThrowIfNegative(value);

_count = value;

}

}

public void Reset()

{

_count = 0;

}

}When you refactor the class to use the field keyword, you’ll run into the following error if you try set the underlying field value in a method:

The only way to fix this is to use the set method on the property as well:

public class Counter

{

- private int _count;

-

public int Count

{

- get => _count;

+ get;

set

{

ArgumentOutOfRangeException.ThrowIfNegative(value);

- _count = value;

+ field = value;

}

}

public void Reset()

{

- _count = 0;

+ Count = 0;

}

}In general, this is considered best practice, since it ensures your value is always validated before being stored. But what if your set method has side effects you want to avoid in certain cases?

For example, the following class raises an event every time the FirstName or LastName properties are updated:

public class Customer

{

private string _firstName;

private string _lastName;

public string FirstName

{

get => _firstName;

set

{

_firstName = value;

RaiseEvent(new FirstNameUpdated(Id, _firstName));

}

}

public string LastName

{

get => _lastName;

set

{

_lastName = value;

RaiseEvent(new LastNameUpdated(Id, _lastName));

}

}

public void Anonymize()

{

_firstName = "ANONYMIZED";

_lastName = "ANONYMIZED";

RaiseEvent(new CustomerAnonymized(Id));

}

}If you need to set the first and last name values without triggering side effects in the set method, for example, from an Anonymize method, then you'll need to stick with manual backing fields.

Targeting Fields with Attributes

If you previously applied attributes to your private backing fields, you need to use slightly different syntax when using auto-implemented and field properties. Consider the following code sample, which applies a custom [WatchField] attribute to the backing field.

public class Order

{

[WatchField]

private string _deliveryAddress;

public string DeliveryAddress

{

get => _deliveryAddress;

set

{

ValidateDeliveryAddress(value);

_deliveryAddress = value;

}

}

private void ValidateDeliveryAddress(string address)

{

// Validation logic throws exception if invalid.

}

}When you refactor the property, you have to use the field: prefix so that the attribute targets the underlying field rather than the property:

public class Order

{

[field: WatchField]

public string DeliveryAddress

{

get;

set

{

ValidateDeliveryAddress(value);

field = value;

}

}

private void ValidateDeliveryAddress(string address)

{

// Validation logic throws exception if invalid.

}

}Notice how the attribute is applied directly to the compiler-generated backing field in the compiled code:

public class Order

{

[CompilerGenerated]

[DebuggerBrowsable(DebuggerBrowsableState.Never)]

[WatchField]

private string k__BackingField;

// ...

} Naming Conflicts with Existing Class Members

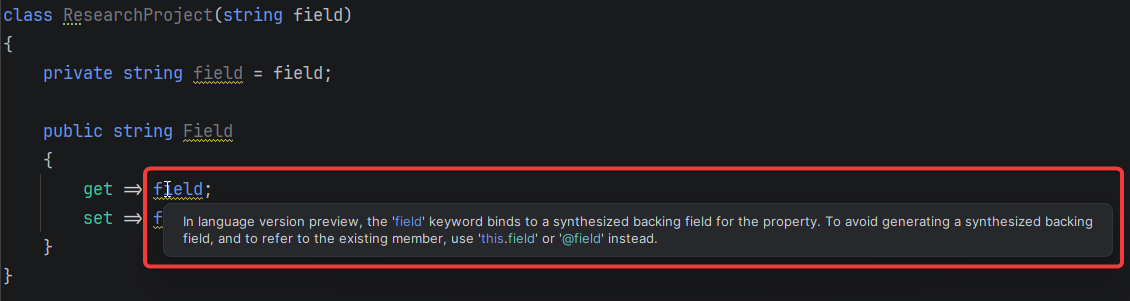

The field keyword hasn’t always been a contextual keyword, and you could use it as an identifier in previous versions of C#. For example, the following code compiles in C# 13 and earlier:

class ResearchProject(string field)

{

private string field = field;

public string Field

{

get => field;

set => field = value ?? throw new ArgumentNullException(nameof(value));

}

}In the snippet above, the field variable used within the Field accessor methods references the private field defined immediately above.

However, when updating your project to use C# 14, you’ll run into the following warning, indicating that using the field keyword inside the accessor will reference a compiler-generated field rather than the existing `field` member.

To fix this, you can refer to the existing field member using this.field or @field:

class ResearchProject(string field)

{

private string field = field;

public string Field

{

// Example of using the `this.` syntax to refer to the backing field

- get => field;

+ get => this.field;

// Example of using the `@` prefix to avoid naming conflicts

- set => field = value ?? throw new ArgumentNullException(nameof(value));

+ set => @field = value ?? throw new ArgumentNullException(nameof(value));

}

}Conclusion

The field keyword in C# 14 helps you avoid unnecessary boilerplate by removing the need for explicit private backing fields. It lets you use auto-implemented properties even when you need custom logic.

As we inspected the generated IL code, it became clear that the keyword is syntactic sugar. The compiler still generates the same backing field and connects it to your property accessors. However, the abstraction does come with trade-offs, which we unpacked in the second half of the article.

This new feature moves C# toward less verbose code by making auto-implemented properties more flexible. Most codebases will benefit from adopting it. Just remember the caveats, especially if you're working with legacy code or reflection-based libraries. Proceed with caution, and ensure you have good test coverage to catch any issues during refactoring.